Introduction

One of my favorite topics to discuss in the performance space is the topic of getting back to the basics, and doing them REALLY well. Especially at the youth ages, but I find myself more and more grounding myself in these concepts even in my advanced and professional clients both in the performance and rehabilitation realms. It’s so important that I can see the concepts on the microscopic level of getting an athlete through a training plateau all the way up to the programmatic level and even into my philosophy in mentoring students and staff. I see it almost every day where these concepts get overlooked by technology, social media trends, mis or underinformed parents, etc. While more challenging than one would expect, stick to these 5 basic concepts of strength and conditioning and performance training and you and your program will find success.

1. Core Principles

Identify and employ core principles. These guide all strength and conditioning programs.

Progressive Overload:

Progressive overload is the gradual increase of stress placed on the body (e.g., heavier weights, more reps, higher intensity). Keep in mind micro and macrocycles of course, but moreover the bigger picture and goal(s) of the athlete. You can accomplish this concept with varying tactics and techniques. One aspect to always keep in mind is doing so with the minimum necessary dose (intensity x duration). I don’t specifically use the Frequency, Intensity, Time, and Type (FITT) acronym per se, but if you boil the program down it should fall into these categories and be similar to the demands of their sports and position. Training and developing an athlete is a steady process with attention to detail over time, not a product.

Specificity:

Specificity doesn’t mean trying to mimic movements, but rather that training should match the demands of the sport or goal(s). This one is surprisingly bland in common practice. In football, your offensive linemen should not be training like your wide receivers. On top of that, the Global Positioning System (GPS) you are using for them is probably not the best indicator of performance, where it may be for your skill players. For us, this is why we invested heavily into High Intensity Interval Training and regularly use Assault Bikes, SkiErgs, and Rowers to get heart rate spikes similar to those that we see in games. Your soccer goalies should also not be held to the same fitness or performance standards as your attackers or midfielders. Your baseball players probably don’t need to run poles as part of their foundational training pillars. Can you mix and match and use as a cross training and something different here and there, yes. But, specificity matters. The SAID Principle (Specific Adaptations to Imposed Demands) is the real pinnacle here. While there is a science to the SAID principle, there is also a major art component. I know a lot of coaches who have mastered one or the other. The ones we hold in the highest regards and are known as the titans of our profession have mastered both the art AND the science.

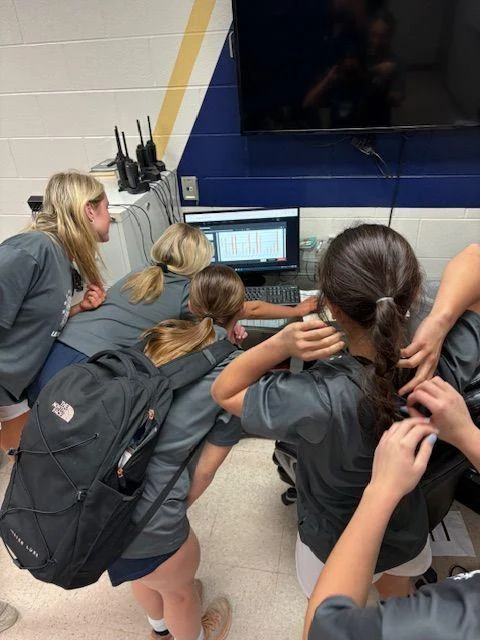

Image: While GPS itself may not be simple. Gamifying and turning it into a competition to get more out of your clientele is. Here our Soccer girls come in before practice to see the previous day’s report. This is a daily occurrence for us as well as “Did I run faster than X, or did I break Y MPH” questions.

Individualization:

The purpose for individualization goes beyond sport and position. Each athlete has different needs, abilities, and recovery rates. This is an especially important and even more challenging component in team settings. Not only that, but it grows in complexity as the team size grows. Take a football team for example. Grades 9-12 you have 100 guys of nearly all body types, training experience, and training loads. Yet, you go into many weight rooms across America and you see a single workout posted on the board. At minimum you should tweak volume, teachable aspects, auxiliary exercise selection, mobility components, and/or recovery tactics. Having a 5 star varsity senior do the same workout as a 9th grade first year athlete in the weightroom is a gross underservice to both.

Recovery and Adaptation:

Muscles and neural adaptations grow and improve during recovery — not during training itself. This is one I overlooked a lot early in my career. I used the level of soreness as an indicator of the quality of the workout I did, or proctored. In reality that is not always the truth, and it’s becoming a weaker and weaker correlation over time. If that was true, I’d walk through the weightroom with a hammer and baseball bat instead of a plan and program. As stated above, identifying the minimal dose to achieve a desired outcome and using it instead of just adding and throwing in exercises to fill time. Twice a week we have a ninety minute training window. If they get the dose they need I’d rather see our strength and conditioning coaches give an additional 15 minutes to rest, recover, get nutrition, etc as opposed to filling the time with a random exercise or task. These kids are stressed and time poor as it is. We need to help with, not add to any of the potential negatives.

Variation:

Changing exercises, sets, or loads prevents plateaus and keeps training stimulating. I get tired of being in the weightroom three days a week for 40-45 weeks of the year. Imagine what it’s like through the lens of a 14-18 year old young lady or young man. Sometimes these changes don’t need to be massive. A classic example for us would be every so often we move our dynamic warm up outside. Same warm up, different scenery. Sometimes our volleyball team does their plyometrics outside on turf, and opposed to inside in the weightroom. On the rare occasion we have a team and parents breakfast as opposed to a 40 minute workout. Yes, you absolutely need to stay consistent and allow time for the body to acclimate to the demands applied to it, but at the same time sometimes a very little variation from the normal can have exponential effects in the positive direction.

2. Key Components of S&C

Identify what the key components are and should be in your program. Then make a very simple cache of each component, being sure to not always use the same and to revert to old habits in uncomfortable situations. We use this very simple chart and do regular check in’s to make sure we are not over emphasizing one quality, or even worse underemphasizing one of the qualities. While it’s not a 1-1 ratio of each, it’s important to regularly monitor your program and the wants, needs, and values of the sports team you are servicing.

A complete and well founded program includes several physical qualities:

Table: List of components of training and examples of how to implement them.

As you can see, these are very basic but when consulting programs or even just on social media you can see an alarming amount of redundancy or imbalance of stimuli. Even further you see aspects of programs that just are not specific or applicable. I’ve yet to find a basketball player where running timed 400 meter runs have translated ideally to the court. Does it hurt them, probably not. Does it maximize their outcomes with the minimal dose, absolutely not. Does it make them a better basketball player, debatably at best. Would watching a segment of film and mimicking their position demands and doing tempo runs or change of direction with decreased rest times similar to those they experience on the court and have them perform a sport specific task during or at the end of each rep be more applicable, I think so 10 out of 10 times.

You will also notice that I don’t have many specific exercises or tasks in the example column. That’s because while specific exercise selection is important in programming, I don’t think it’s the pinnacle. It’s too easy to get into the weeds and into biases. I like to program concepts and stimuli goals or targets, then fill in with specific exercises, not the other way around. The days of building weeks worth of workouts around a single lift are, or at least should be, gone. I also use this chart as a way to check balance between stimuli. You never want to get too heavy in a single aspect, but rather switch between them and vary the intensity and load of each to optimize the body’s adaptations and to avoid burnout and plateaus. I use this more as a way to check me and to bring subconscious biases to light, than to program a workout for others.

3. Training Structure

This is another one that’s evolving, but I think the basics are still true and time tested. For us here is a typical structure of an S&C program or session:

Warm-up. Raise heart rate, activate muscles, address mobility, and prep for movement.

Key Examples: dynamic stretches, mobility drills, activation exercises. We avoid static stretching except when there is a specific medical need. Otherwise the research is pretty substantial on decreased force production and short time to effect while also being long to achieve a minimum response. We do static post activity, if needed. This warm up should be a minimum of 10-15 minutes and mimic the demands of the session itself. Emphasize that – it’s not erratically blowing a whistle to get guys moving, or just going through the motion – it’s a focused, attention to detail, and diligent task. Too many times I see coaches cut warm up short. Then wonder why musculoskeletal injuries are increasing, soreness is lingering, and major joints (particularly ball and socket joints – hips and shoulders) are getting tight. For 30-45 minutes a week we can alleviate a number of those “issues.” Just to math it; there are 10080 minutes in a week. With 0.44% of the minutes in a week we can address major biomechanical and physiological issues. So yes, please cut practice drills, film, etc short 1% a week to get an exponential return on time investment.

Skill or Speed Work Performed when the athlete is fresh and well warmed up and tuned for activity.

Key Examples: sprint mechanics leading into sprints, both resisted and/or top velocity, agility drills, plyometrics, and change of direction drills. These are high intensity and for the most part heavy nervous system loads. I believe getting to top speed for 1-3 reps 3 days a week (this can include competition if able to measure) is the key to steady top speed progression. We also see a significant decrease in cramps and neuromuscular dysfunction when exposed to these forces and stimuli. In over 3500 varsity football plays over 5 years since instituting this training method We have had to stop play for 11 plays playing in the Alabama heat and humidity. 9 of those 11 plays the athlete cramping did not get to their top speed in that training week outside of the game itself. They were not prepared neurologically to the strain on the system of top speed in a high stress environment

.

Image: Your weightroom is a place of education. We live by the ethos: “If you give a man a fish he eats for a day, you teach a man to fish he eats for the rest of his life.” Here you can see a good start of a countermovement jump (Picture 1), a good finish (Picture 2), and one where there is wasted energy resulting in less than optimal performance (Picture 3). This is a great teachable moment for both the coach and athlete. Video it, break it down with the athlete, practice it, then re-assess it. Do this over time to get many small victories and to build rapport with the athlete, and their stakeholders (coaches and parents/guardians). If they see you pouring into their athletes or kids, you will get their support. This is a process, not a product.

Strength Training: The main portion uses resistance training.

Key Examples: pushes, pulls, squats and their variations, bench presses and their variations, olympic movements, etc. These are the peak of the workout – where intent is highest, attention to detail is at its highest, and when the most demanding portion of the stimulus is applied. This is where deconstruction of the sporting and position demands and applying a progressive overload stimulus occurs. It’s also where some coaches fall into a routine and sometimes worse, revert to old habits. Keeping an organized program is the keynote here. Be able to see what you have done and what you plan to do and keep the real emphasis clear and direct. See the Core Principles section above, and within your own program.

Accessory Work: Correct imbalances and target weak links.

Key Examples: single-leg work, core exercises, arm care. I like to program super sets using an exercise number = number of athletes in group – 1 formula. If we have 4 athletes in a group we program supersets of 3 exercises for example. One exercise is the strength exercise, the 2nd and 3rd are accessory exercises, and the 4th is a rest / spotting role. In my experience at the youth and even in the advanced athletes to an extent, overemphasizing major lifts encourage established bad habits just as much as they fix them. Therefore we do an accessory to the main lift in the superset in a 2-1 ratio. This is also how to get some buy in. For example while bicep curls do not translate to many on field/court outcomes – we program them or a variation every other week so the guys can “get a pump” and get some excitement.

Conditioning: Energy system training for endurance or sport demands.

Key Examples: intervals, sled pushes, or circuits. These are surprisingly rare for us. We mostly program these as cross training or to get a higher strain in a short time constraint. The one exception is our High Intensity Interval Training. On a low level we match work time and rest time to demands of position and sport as best possible. On the individual level we monitor heart rate so instead of work-rest ratios we based time off heart rate responses. We are early in this but have seen major success in specific populations such as our football offensive linemen. To take it to the next level we program in SHREDmill sprints as well.

Cool Down & Recovery: Stretching, mobility, and low-intensity work.

Key Examples: foam rolling, band stretching, dynamic mobility (we like hurdle mobility). Much like warm ups I see far too many programs and coaches cutting this part short or just not performing it at all. In that light, this aspect is probably the lowest lying fruit for many coaches. Allowing time for the body’s systems to gradually return to resting levels after being elevated is extremely important when it comes to recovery. We phrase it as recovery for the next session or game/match starts the second the workout ends, so get off to a great start with a cool down, hydration, and nutrition.

4. Supporting Factors

These are basic aspects that are essential to have a solid foundation for your program.

Nutrition:

Fuels performance and recovery (protein, carbs, hydration). It also adds an excellent metric to address a goal. It’s also very easy to measure. If an athlete weighs 180lbs and wants to get to 190 in 6 months this is a low lying fruit on how to educate them on how to do it safely and effectively and have built in benchmarks along the way. We use these components as a way to build rapport with our athletes and parents. Once you get good at the basics you can add components like body composition with the resources available to you.

Sleep & Recovery:

Essential for adaptation and avoiding overtraining. One of the strongest performance enhancing drugs you can utilize is proper and consistent sleep. If it’s one thing I have learned in my time in the secondary school setting it’s that kids these days are stressed (not always a distress, there’s some eustress also) and that they do not sleep well or enough.

Monitoring:

Track progress (strength tests, heart rate, jump tests, etc.). This is a massive spectrum. The basics are really simple. Attendance and body weight are the two we see as most important. At the same time you can spend thousands of dollars and hours of time monitoring macro and micro metrics. Do what you can within reason and your means. Always be sure to stick to your core principles. Never collect data just to collect data. You’re sure to achieve paralysis by analysis or completely miss the objective if you are collecting data just to collect data. Always have a clear purpose, methods, and outcomes for any athlete or program monitoring you choose to employ.

Injury Prevention:

Incorporate movement quality, mobility, and load management. I always say the best rehabilitation I ever had to do is the one we prevented by incorporating movement quality and mobility and more contemporarily loan management. It’s also true that we have never had a pitcher on the disabled list win us a game. Injury prevention is key to the longevity of an athlete.

Image: Getting injured does not mean avoiding the weight room. One way we break up the monotony of a long term rehab as well as work on foundational skills is quickly getting back into the weightroom after injury. This case here is 8 days post Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction doing bench press using Vitruve as feedback. The mental aspect of getting back in the weightroom with their team is very important.

5. Conceptualizing The Role of a Strength and Conditioning Coach Within Your Context

This one is so incredibly important and basic that I think our world has overcomplicated it. Mostly for reasons out of our control like administrative views, values of stakeholders, and geographical biases. When conceptualizing the role of a strength and conditioning coach, what it should be and could be are largely debatable. Not only that but what the role says in writing is not always what the role actually looks like in application. Not that this is a bad thing, it’s just that programs evolve and roles subsequently also evolve. However, there needs to be a foundation and tenants that should define the strength and conditioning role, and how they can support the student-athletes, coaches, programs, and mission and vision of the school or company itself. Regardless, role delineation needs to be a keystone concept and customized to the stakeholders you service. Especially if you are in an administrative capacity. But, also true if you are not and utilizing the concept of counter power and especially if your administration has a growth mindset. After spending weeks to months working on these, here is what we settled on:

Primary Roles of a S&C Coach:

- Designs safe, effective programs. The primary goal is to maximize performance while minimizing time-loss injuries.

- Monitors performance and progress. Use contemporary science, techniques, and systems to guide your program. Then use objective measures to accurately assess its effectiveness while minimizing biases. There should be a constant implementation, assess, adapt, re-assess, repeat cycle within the performance program.

- Educates athletes on training habits. The younger the athlete, the more important this is. Don’t forget the why! Always teach the why behind what you are implementing. If you give a man a fish he eats for a day. If you teach a man how to fish he eats for a lifetime.

- Collaborates with sport coaches, sports medicine, administration, and stakeholders (parents, guardians, sponsors, etc.). Don’t ever work in a silo or a vacuum. Work together to learn and implement best practices. This should always center around what’s best for the athlete(s). Be sure to check your ego, biases, and any other baggage that may or may not be present. Everything we do is to support the athlete, program, and mission and vision of the entity.

An honorable mention that I firmly believe in, but also understand that it doesn’t fit all models is that the strength and conditioning coach should only be a strength and conditioning coach. Not a strength and conditioning coach and a football position coach, study hall monitor, assistant baseball coach, history teacher, and so on. To truly understand and keep up with the ever evolving science of the field, the strength and conditioning coach needs to be focused on that and given the proper time and space to master the art. Strength and conditioning is truly an art and a science. By dividing their attention you are only limiting their impact on supporting the athletes and programs. However, I do understand that in some contexts that is just not possible.

In summary, aspects like programming, technology, techniques, etc. are all important. However, far too many times those aspects get overemphasized while the basics are lacking or forgotten about. If you go and find an excellent coach you can guarantee that they do the basics really well then build off those basics to build a highly functional program. The basics are the foundation of greatness.

The post Getting Back to the Basics of Strength and Conditioning and Performance Training appeared first on SimpliFaster.